Robert Fitzpatrick, the former president of the California Institute of the Arts who spearheaded the acclaimed 1984 Olympic Arts Festival in Los Angeles, has died. He was 84.

Fitzpatrick died Sept. 30, CalArts said. No cause of death was given.

“The world lost a fierce champion of artists and of the critical role arts play in society; an unabashed optimist who consistently demanded — and achieved — a degree of trust and independence that enabled him to create space for the arts on a level we seldom see,” CalArts President Ravi Rajan said in his remembrance.

“He trusted artists, and it served us — and the world — very well.”

Fitzpatrick was named the second president of the school in 1975. The institution, originally conceived by Walt Disney as a sort of “Caltech of the arts” to nurture talent and creativity across artistic disciplines, opened its doors to students in 1970 but was soon mired in financial woes.

During a talk held as part of the Valencia school’s 50th anniversary celebration in 2023, Fitzpatrick reminisced about his path that led him to taking the job. A spirited storyteller, he recounted how he had been terrified as he arrived for his first day and how faculty members stopped by his new office to offer their support and well wishes.

Among them was director Alexander Mackendrick, the dean of the film school at the time. Fitzpatrick said Mackendrick pulled him out of his office to observe some students before offering a bit of advice that helped guide his approach to the job.

“You’re not here to encourage success,” Fitzpatrick said Mackendrick told him. “You’re here to let [students] fail intelligently and learn and take risks. So don’t reward success. Give them the courage to try and fail.”

Born in Toronto in 1940, Fitzpatrick arrived in California by way of Baltimore. He studied at a Jesuit seminary before heading to Johns Hopkins University to pursue a degree in medieval French. He would go on to work at Johns Hopkins, where he eventually was named the dean of students. He was elected Baltimore’s then-youngest city council member in 1972. He told Time magazine in 1974 that one of his goals was to be a college president.

Described in L.A. Times coverage as a “high-energy, fast-moving arts impresario” as well as “a restlessly domineering visionary and brilliant fundraiser,” Fitzpatrick was said to have “quickly stirred things up” at CalArts with “his trademark combination of bluntness and idealism.” He helped to bring financial stability to the institution — raising $58 million during his time as president — in part by overhauling the board of trustees. Among other changes he brought: He instructed the faculty to start giving students grades.

“For 13 years I had one of the most interesting jobs on the face of the Earth,” Fitzpatrick said in 1990 while looking back at his tenure at the school, which also saw the establishment of CalArts’ character animation and jazz programs. “I was the orchestra conductor, if you will. … What an orchestra.”

While at CalArts, Fitzpatrick was tapped as director of the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival. Times classical music critic Mark Swed recently wrote about the 10-week-long festival, which “dramatically changed our city not only culturally but physically, economically and, maybe more important of all, psychologically.” The ambitious artistic programming — and the large crowds drawn to events — made Los Angeles think of itself more as a place of culture, Swed said. “The festival so transformed how Angelenos felt about their city that suddenly grand projects” — like building a grand concert hall — “seemed feasible.”

Fitzpatrick would go on to propose the Los Angeles Festival, a follow-up international arts festival held triennially from 1987 to 1993.

His success at CalArts as well as with the Olympic Arts Festival led Fitzpatrick to being named president of Euro Disneyland, now known as Disneyland Paris, in 1987. He saw the themed entertainment resort through its opening (as Euro Disney) in 1992 before leaving the company the next year.

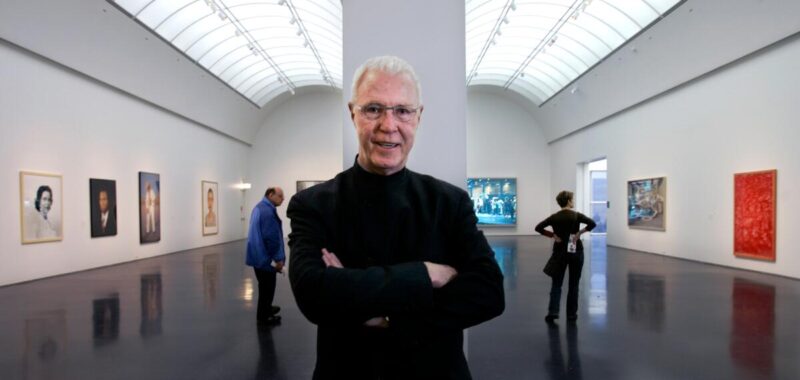

Fitzpatrick’s subsequent work included consulting, serving as the dean of the School of the Arts at Columbia University and as the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

“In my career I have believed strongly in commitments of intensity, not of duration,” Fitzpatrick said in a 2015 interview with Flash Art.

Before leaving Los Angeles for Paris in 1987, Fitzpatrick discussed how his approach to organizing that inaugural Los Angeles Festival was to seek out art that troubled him, that unsettled him or that could challenge audiences.

“I’ve been very adamant in my own personal definition of what’s appropriate for a festival in this city,” said Fitzpatrick. “That is that it be things that we wouldn’t normally get access to, things that are somehow special, somehow different, and will provoke us, stimulate us into understanding things we might not have understood.”

Fitzpatrick is survived by his wife, Sylvie Fitzpatrick; children Claire, Joel and Michael Fitzpatrick; sister Sharon Denny; brother Murry Fitzpatrick; and six grandchildren. CalArts said it was planning a memorial, details of which will be announced later.