Then the second terrible thing began to happen.

“By the evening, we kept getting calls,” Ibrahim Hussein says. “We were told that the social media was going berserk, that something’s not right. Something’s brewing. And that you need a lot of protection.”

Hussein assumed there must be a misunderstanding. He’d lived in Southport for 20 years, and one thing he particularly enjoyed was the lack of things brewing. “A very nice, sleepy town,” he says. “Full of old people and retired people, and there is nothing happening here. Nothing. So when I decided to retire, I came here.”

He used to keep a mini-market in London, and now he is the chairman of the Southport Mosque and Islamic Cultural Society Centre, which has been there even longer than him, 30 years. It’s in a building in the middle of town, a short walk from the train station and the wide medians of Lord Street. They—Hussein, the mosque, the people who worship there—are as much a part of Southport as Victoria Park or the lawnmower museum.

“The murders happened just about three minutes’, four minutes’ walk from here,” he says. Indeed, the corner where the police cordoned off Hart Street for the memorial is halfway between the mosque and the crime scene. “Obviously, we were all devastated, just like everyone else.”

He expected to attend the vigils, to lay flowers at the memorial, to stand with the other clerics and mourners. He wanted to do those things, wanted to bring comfort to his community as best he could. But the night before, just hours after the murders, he started getting calls. “So we started to watch some of it and hear some of it, and we got a few more messages,” he says. “And this is on that very same evening.”

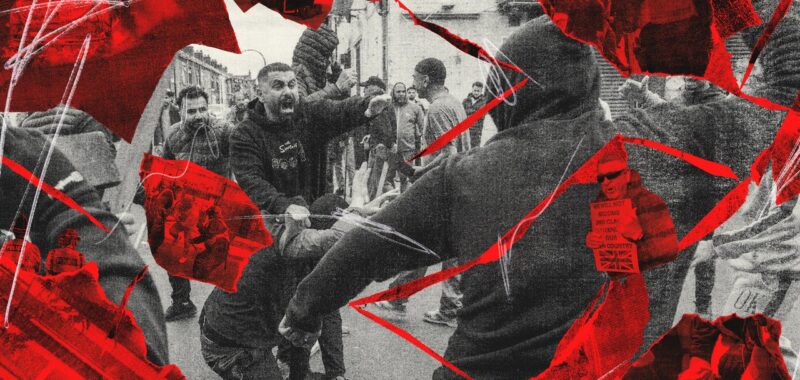

Earlier Monday afternoon, a neo-Nazi calling himself Stimpy—the Nazi flag and Nazi armband were clues—had created a channel on Telegram called Southport Wake Up. Within hours, someone posted a graphic of a bloody handprint beneath the words “Enough is enough.” Below, stacked in five lines of bold type, were: “PROTEST, Tuesday 30th July, 8pm, St Luke’s Road, Southport.”

The mosque is at the corner of Sussex and St. Luke’s roads. A second graphic showed a man wrapped in a gray balaclava with a hoodie pulled tight around his head. “No face, no case,” it read. “Protect your identity.”

That struck Hussein, initially, as peculiar, possibly absurd: The mosque’s only connection to the murders of three little girls is that it happened to be in the same town. At that point, only hours after the attacks, authorities had not released the suspect’s name or any details other than that he was male and had a knife. Publicly, he was a cipher.

Yet social media was full of certainty. By nightfall, a writer with The European Conservative wrote on X that “a migrant stabbed numerous children at a holiday nursery.” The American right-wing commentator Andy Ngo, who wrote a book about antifa’s plan to destroy the United States, reported the news straight to his 1.6 million followers—mass stabbing, suspect apprehended—but then added this odd context: “Last October, an illegal migrant stabbed an elderly Englishman to death in Hartlepool for Islam & Gaza.” Ngo did not explain why that was relevant. Accused rapist and alleged human trafficker Andrew Tate, who nonetheless has 10.5 million followers on X, began a three-and-a-half-minute rant with: “So an undocumented migrant decided to go into a Taylor Swift dance class today and stab six little girls.” Even one of the replies to Patrick Hurley’s statement included a screenshot from a fake news site that claimed the suspect was a teenager named Ali al-Shakati who’d sneaked into England by boat and “was on an MI6 watch list and was known to Liverpool mental health services.”