In the bustling streets of Amritsar, India, the markets are lined with shops full of colorful tapestries and sweet treats like warm local chai served in clay mugs. But the real treasures are kept behind closed doors. Beyond stacks of gnarled logs, inside unsuspecting brick buildings off the main streets, generations of master craftsmen carefully carve, sand, and polish intricate chess pieces, carrying on a long legacy in the country where the earliest versions of chess were played over 1,500 years ago.

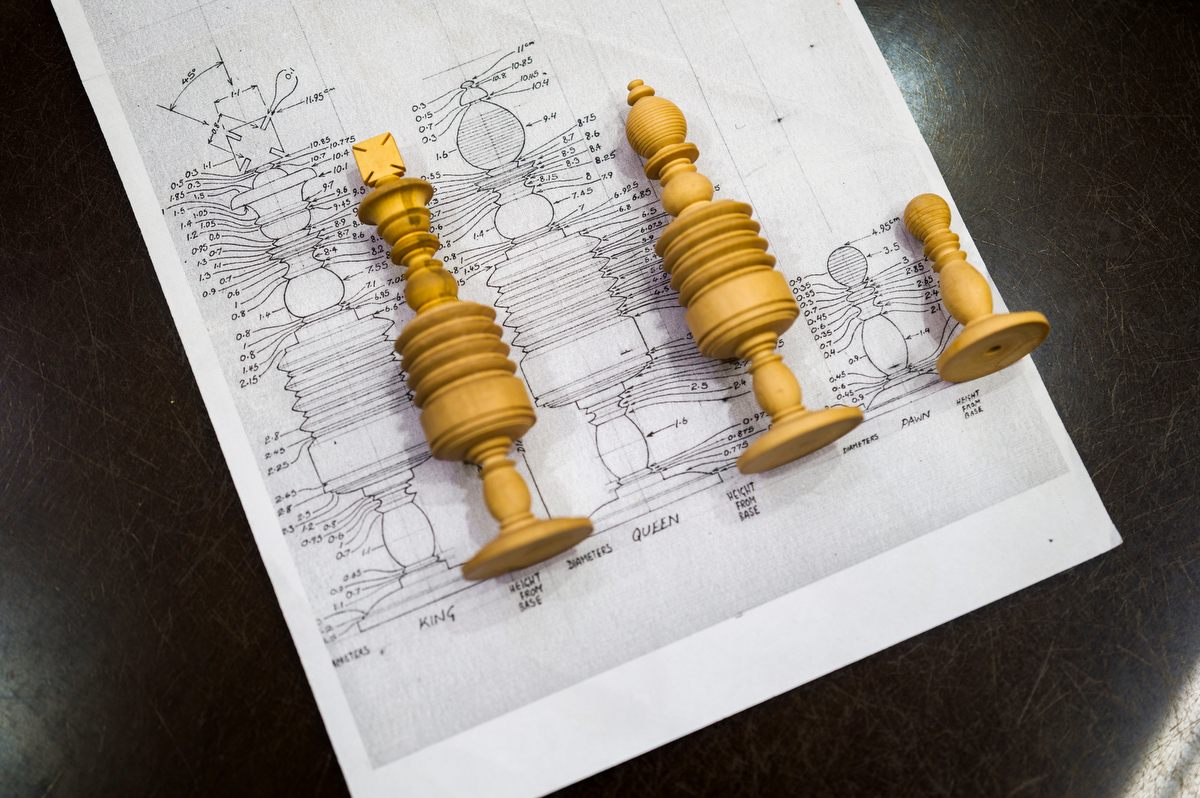

These are no basic sets. The pieces make up elaborate professional and collector’s chess sets that sell for up to $4,000 U.S. dollars on the international market. That price is well deserved. Each set is a collective labor of love, with every component handcrafted by a man who specializes in one type of chess piece. (Traditionally, women are not chess carvers.) There are pawn makers, queen craftsmen, and the most coveted—the knight carvers.

“The knight carvers are only knight carvers,” says Rishi Sharma, CEO of the Chess Empire, India’s oldest and largest chess manufacturing company, which was founded in 1962. “The person who is making the queen, we don’t give him the pawn. Otherwise, he’s going to ruin it.”

Of all the chessmen, knights are considered the most difficult and require the most skill to carve. While pawns and other pieces can be shaped under lathes, the knights—resembling horse heads usually with wild flowing manes—are carved completely by hand. A chess carver won’t graduate from pawn to knight or any easier piece to harder ones, but instead will learn his craft from the start of his career, usually from their father or a mentor from one of the well-established chess companies. Surinder Pal, a knight carver at the Chess Empire, learned from his father at 18 years old. Now, he has been working on the craft for over 35 years. With his advanced and highly specialized skill, he can make up to 30 simple knights a day, or spend up to three days on a single ornate knight.

Today, chess pieces are carved from local species like boxwood or imported trees like rose and dogwood. But they were once made of a far more elusive and illicit material. Amritsar was originally known for its ivory carvers, who produced everything from hair combs and jewelry to furniture and sculptures. And of course, chess sets. After the international trade of ivory was banned in the 1990s, the craftsman turned to the similarly smooth but far more accessible medium.

With raw materials readily available, it’s the demand for these fine chess sets that determines how many are produced. And demand has fluctuated in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic left many people secluded in their homes, leading to a boost in demand for many indoor games, says Sharma. In October 2020, that enthusiasm for chess was compounded by the release of The Queen’s Gambit, a series about a fictional American chess prodigy. “The Queen’s Gambit had a very big role in spreading awareness of chess,” Sharma says. “And after that, we see a big boom.” Despite the show’s creator stating they have no plans for a second season, Sharma stays hopeful. “We hope the next season comes as soon as possible.”

That initial excitement has since faded, he says. With economic impacts and trade restrictions from ongoing wars around the world, the demand for high-quality chess sets has taken a hit, Sharma says. As producers in China and other countries circulate more plastic and inexpensive sets, the ornate wooden craft has become more of a luxury. But for some, the price is well worth it. “You won’t get the feeling of that craftsmanship in those plastic chess sets,” Sharma says.

While he is optimistic that international demand will return, they’ve seen a rise in interest within India. The brain-engaging game became popularized in elite private schools across India in the early 2010s. Due to great success—including fostering Gukesh Dommaraju, who became the youngest world chess champion in December 2024—the initiative is now spreading to government-funded schools as well. While women may not be carving chess pieces, young women are playing the game—in September 2024, the Indian men’s and women’s teams both took home gold at the Chess Olympiad.

Despite the game’s rise in popularity, young people aren’t clamoring to learn how to make the sets. “The younger generation is not interested in this kind of handcraftsmanship,” Sharma says. “They want only white-collar jobs to do in the malls or offices. They don’t want to come work in this sawdust.”

Still, for those few who do take an interest in the craft, the Chess Empire is always willing to teach.