When the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum closed in 1935, its cemetery was unceremoniously forgotten. The plant life became tangled overgrowth, wooden grave markers deteriorated, and the thousands of marked and unmarked graves there lay untouched for decades.

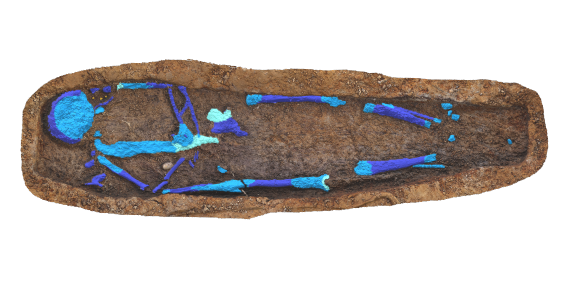

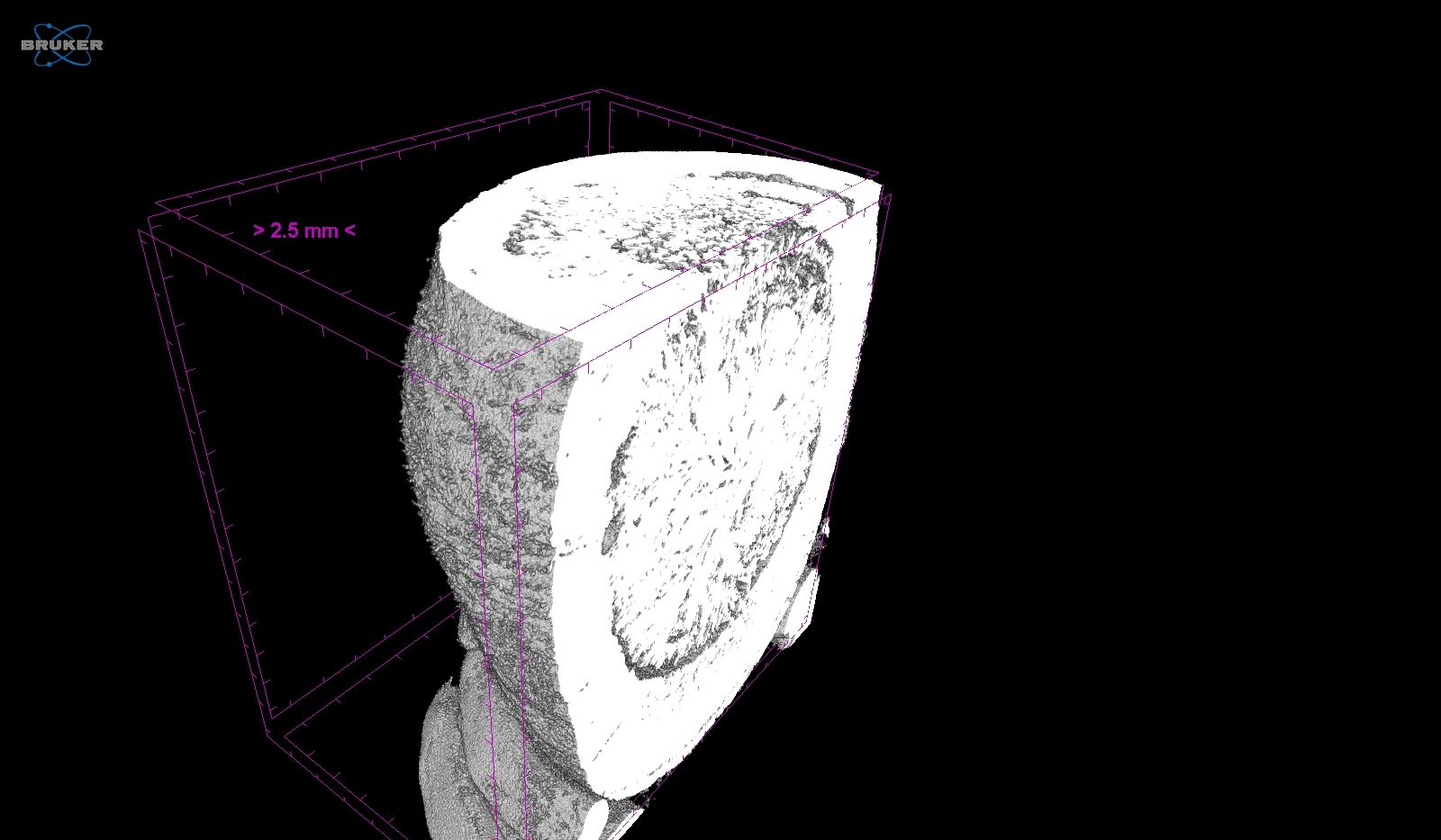

By 2012, the land became part of the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center. When the institution rediscovered the graves during construction on campus, it started the Asylum Hill Project to research the history of the cemetery while respectfully studying, memorializing, and moving the deceased to a more suitable location on campus. As researchers began excavating the first 100 burials, they discovered an archaeological oddity among the remains of one individual: a stony-beige colored object, about the size and shape of a quail egg (about two inches long and one inch wide), sat in the soil, right in the middle of this person’s torso. It was oddly light for its shape and size.

Initially, no one knew what it was. “Everyone just stood around and had theories,” says Jennifer Mack, the lead bioarchaeologist at The University of Mississippi Medical Center and the Asylum Project. “Someone thought it was a calcified cyst, someone else thought it was a gallstone, and I thought, ‘that’s way too big to be a gallstone.’” Mack took the object back to her office. Later, a retired surgeon on the team visited her. “I said, ‘hey, we found something interesting,’” Mack recalls. “He came over, and as I was opening the bag, he said ‘I think that’s a calcified gallbladder.’ Because as a surgeon, he had seen them on multiple occasions before.”

The team later confirmed it to be a perfectly preserved calcified gallbladder, also known as a “porcelain gallbladder.” The team recently published their discovery in The International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. It’s the first porcelain gallbladder to be published in an academic journal as an archaeological finding.

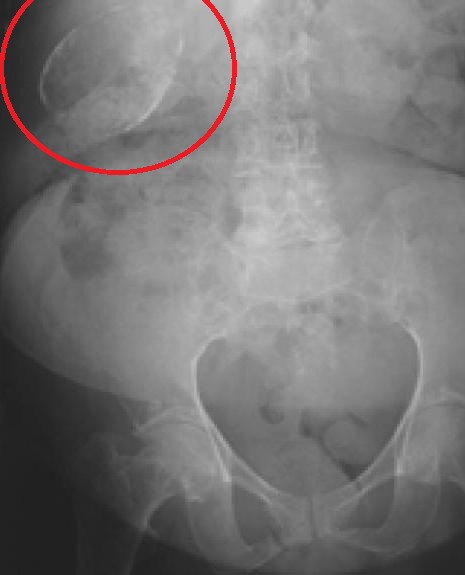

A porcelain gallbladder is a relatively rare and irreversible condition where parts or all of your gallbladder, the organ that stores the bile made by your liver and aids with digestion, calcifies and hardens. It’s named that way not because the organ becomes ceramic, but because in living or recently deceased individuals, a calcified gallbladder takes on a whitish blue color. It’s entirely possible for a person with porcelain gallbladder to not know they have it—people with it are often asymptomatic and can live with the condition. Though, people with a porcelain gallbladder often have it removed, as it can be a risk factor for cancer.

Researchers haven’t come to a consensus on why or how a porcelain gallbladder occurs, but it’s thought that chronic inflammation can trigger the calcification process. Interestingly, even though there are plenty of other places throughout your body and in the gastrointestinal tract where chronic inflammation can happen, “it’s not like we get ‘porcelain esophagus’ or ‘porcelain stomach,’” says Kurt Schaberg, an anatomic pathologist at the University of California, Davis. “We don’t know specifically why the gallbladder turns porcelain, but it famously does.”

Mack and her team know that the individual with the porcelain gallbladder was an adult of middle to old age, but not much else. “The classic scenario of a porcelain gallbladder would be an older woman,” says Schaberg—statistically, that would make the most sense.

Normally after death, all parts of a gastrointestinal tract would decay and rot away. Schaberg says, “It’s kind of interesting to see a part of the GI tract survive due to these calcifications.”