Scott Nicholson is trapped. He’s stuck in a submarine—and it’s sinking. Water is pouring into the room, and he needs to plug the hole before he and his crew drown. Time is ticking, and the water is relentless. Luckily, Nicholson teaches game design. In just a few short moments, he’s able to solve a puzzle that triggers stoppage of the water, saving the crew and winning the game. This is one of 200 escape rooms that Nicholson has played in the past year.

The man doesn’t do it just for the love of the game—Nicholson is a bonafide professional. His ability to solve the underwater puzzle is something he calls a “hero moment,” and they’re integral to the success of an escape room. He should know; he’s the foremost expert on escape room design and science and the director of the Game Design and Development Program at Canada’s Wilfrid Laurier University. He’s been teaching an escape room design class for the past six years.

Escape rooms might seem like casual entertainment, but there’s actually science and a very serious global competition involved. Called Top Escape Rooms Project Enthusiasts’ Choice Awards (TERPECA), the competition gives annual awards for the best escape rooms in the world.

Nominated rooms include games like 60 Seconds to Escape in Gurnee, Illinois, involving skeletons popping out at people down hallways, or Madness Toledo in Spain, featuring biohazard spills, unleashed monsters, and a huge Alien-esque creature taking up most of a room, ready to mow participants down with its toothy jaws. Diego Esteban, the owner of Madness, describes the competition as “the Oscars of escape rooms.”

It’s a pretty apt description. Just like all members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences can nominate movies for Oscars, all qualifying escape room enthusiasts can nominate rooms for TERPECA. “Qualifying” is the important word there; in order to nominate, you need to have played 200 room rounds (which could mean the same room 200 times, though most people spread it out some). To vote on and rank the finalists, members must play 100 rooms.

“The idea is that we’re collecting input from experienced escape room enthusiasts from around the world,” says Rich Bragg, founder of TERPECA and a former Guinness World Record holder for most escape rooms played in one day. “We have a pretty strict application process. People have to demonstrate that they’re legitimately an enthusiast.”

The competition whittles the nominee list from 1,000 down to just 100 top escape rooms in the world. Lately, TERPECA-winning rooms have had a certain style, one that’s dark, gritty, and grim, say David and Lisa Spira, the couple behind the website Room Escape Artist, where they review escape rooms and maintain a database of operating escape rooms in the U.S. But they do see the aesthetic starting to change.

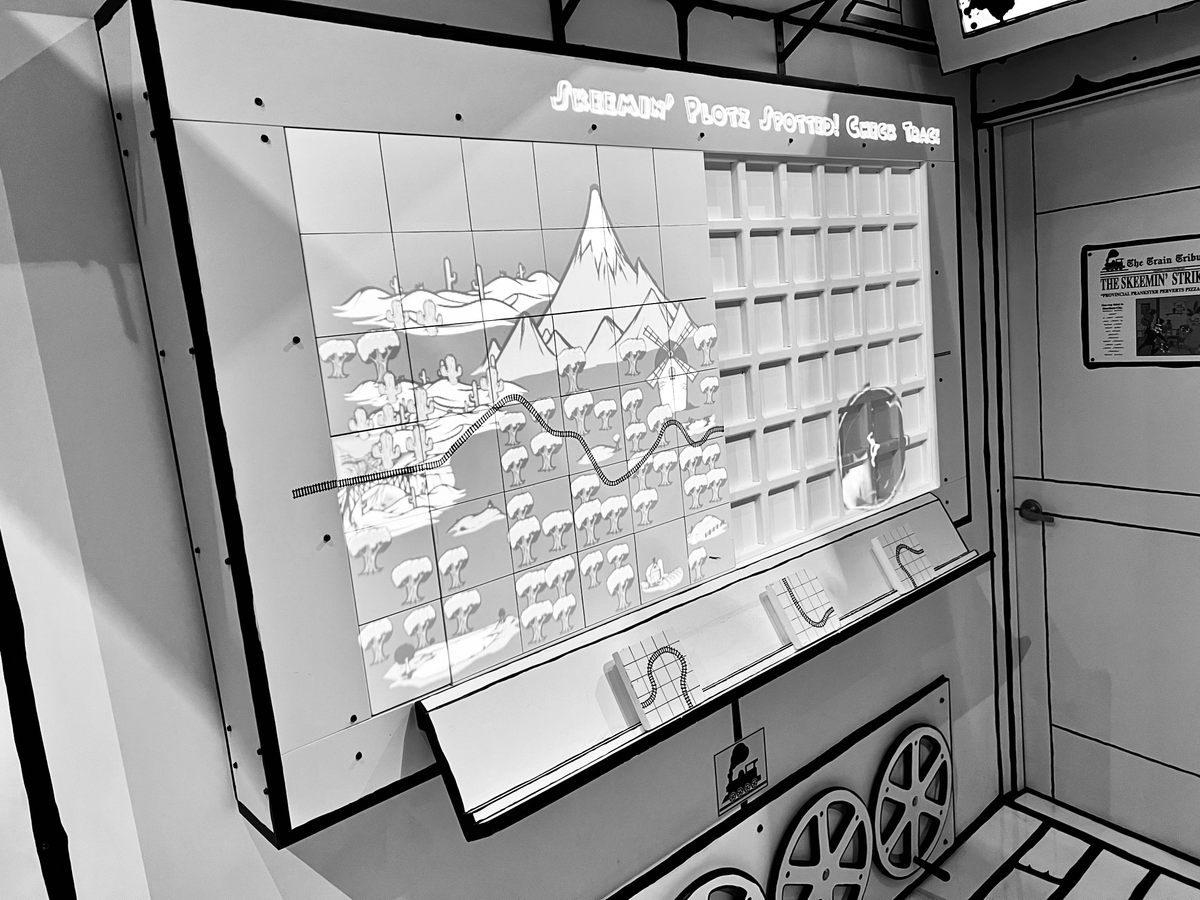

“There’s been a slow shift, adding a lot more whimsy and playfulness into the rooms,” says David. “There’s a game in Kissimmee, Florida that just did well called ‘Crazy Train: The Ballad of Skeemin’ Plotz.’ It’s a black-and-white cartoon escape room.”

Lisa also mentions The Dome in Bunschoten, Netherlands, which took second place this year, as a perfect example of a TERPECA-style room.

“The premise of that game is that you are being administered hallucinogens and put inside of an experiment,” David says. “While they do not give you any drugs, they do make you believe you are hallucinating through set design and technology. You feel like literally anything can happen in this space, because the things that happen to you are so unexpected.”

Production value is high in the winning rooms, with extensive sets, actor interactions, fun technology, and multi-hour games.

“It’s somewhere between art and mad science,” David says.

He may be joking, but there is a surprising amount of science that goes into creating them. A methodology called Escape Room Theory dictates how escape rooms are designed and built. The theory consists of a series of “rules” designers are encouraged to follow—like ensuring each item is used only once (or there’s only one answer to a specific puzzle), making individual puzzles solvable in five minutes or less, and allowing for non-linear puzzles, meaning that one item in a room doesn’t necessarily solve the puzzle you work on in another room. The goal is ultimately to not frustrate participants or lead them down a road that’s tedious or unsolvable.

Escape room expert Errol Elumir boils this down to what he calls the Escape Room Player Loop, which is the path players take toward the solution of the room. It’s broken down into seven sections (Identify Gates, Collect Clues, Select Gate to Work On, Solve Puzzle, Complete Puzzle, Input Answer, Repeat Loop) where frustration can go off the rails for players. Factoring in both escape room theory and the player loop make for a game that isn’t necessarily easy, but is entertaining and able to be solved.

Psychologically, escape rooms are all about developing an immersive story experience where people feel necessary to the success of the mission, and avoiding ludonarrative dissonance.

“Ludonarrative dissonance is where you have the players doing something that doesn’t connect with who they’re supposed to be playing in the game,” Nicholson explains, noting that things that don’t make sense will take players out of the experience of the game. “I’m supposed to be a good guy saving the world, so why am I ransacking this house of the people that I’m supposed to be saving? It’s like Zelda: ‘I’m here to save the world and save this village, but first I’m going to break all of your pottery and take all of your money.’”

And each escape room absolutely has to include hero moments, Nicholson says. These are times during the game when a player feels like they have a specific skill to contribute.

“You want to have that moment where the person who is good at math does something that no one else does, and they have a hero moment,” Nicholson said. “Then you want to have that moment where the person that has good dexterity gets to throw something or do something physical, and they have a hero moment.”

This involves the taxonomy of player types created by University of Essex professor Richard Bartle in 1996. His taxonomy breaks down players into four categories: Diamonds, who want to win; Spades, who want to hunt around for information; Hearts, who want to empathize with and help other players; and Clubs, who want to play against other players. Alastair Aitchison, a writer for Game Developer Magazine, translated this to escape room stereotypes with the terms Achievers (Diamonds), Explorers (Spades), Socializers (Hearts), and Killers (Clubs). Ideally, an escape room would be tailored to include puzzles or clues for each player type.

Escape rooms haven’t always been this scientific, though. In the early days, the industry was more of a locked-door, escape-the-room experience. Now it’s more of a problem- and puzzle-solving expedition. And no doors are ever actually locked anymore, a rule which fully changed after a 2019 fire in Poland killed five teen girls who were trapped in the game they were playing.

The industry continues to change as well, with new developments like Boda Borg experiences, where it’s a series of rooms you have to get through, and if you mess up on any room after the first, you have to start all over again.

For now, though, escape room designers will continue to make what the Spiras call “TERPECA bait.” It costs designers upwards of $100,000 to $200,000 to fully create the room, but the end result is always a “dark, gloomy, brooding game,” David Spira says. “It’s flirting with horror themes or it might cross over into horror. There is a level of polish; there might be performers involved. There is definitely a TERPECA look.”